1306-1329

Scotland's hero King, the renowned Robert the Bruce, was born into the Scottish nobility on 11th July 1274, at Turnberry Castle in Carrick, Ayrshire. Robert was the son of Robert the Bruce, Lord of Annandale and Marjorie, daughter of Niall of Carrick and Margaret Stewart, herself the daughter of Walter, High Steward of Scotland.

The Bruce family was not of native Scots origin but had its roots in Normandy, a Robert de Brus had come over to England with the army of William the Conqueror. William had rewarded De Brus by granting him lands in Yorkshire but the family had added to this inheritance by acquiring considerable lands in Huntingdonshire and Annandale, Scotland. Robert's mother's family was of Scots Gaelic descent.

Turnberry Castle, birthplace of Robert the Bruce

Following the extinction of the royal line of the House of Dunkeld, no clear successor existed to the throne of Scotland, a period known to history as the First Interregnum. The English King Edward I was asked to decide between the many candidates who claimed the Scottish crown, which included Robert's grandfather Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale , he selected John Balliol, who strictly speaking, had the slightly better hereditary right. Balliol was effectively a puppet King, set up to be manipulated by the formidable Edward and to rule Scotland according to his wishes.

Robert the Bruce's claim to the throne of Scotland derived through his great-grandmother, Isabella, the daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon, grandson of David I. In 1296 King John Balliol was humiliated and forced to abdicate by Edward and there followed a period when there was no King in Scotland for ten years, the country was instead ruled by a series of Governors, this period is known as the Second Interregnum. When Robert's father died in 1304, he made a pact with John Comyn the Red, the nephew of John Balliol, about the succession to Scotland's throne.

Comyn proceeded to treacherously betray Bruce, by informing the English King of their secret plans, as a result of which, Bruce narrowly escaped capture by the English.

Robert the Bruce

In retribution, Robert furiously attacked Comyn at an arranged meeting at the Greyfriars church in Dumfries. Possessing a savage temper when roused, he stabbed Comyn to death in a frenzied rage within the church itself, for which he was excommunicated by the outraged Pope.

He was crowned King of Scotland by Isabella, Countess of Buchan, at a ceremony at Scone Abbey on 25th March, 1306. The ancient and sacred Stone of Destiny used at the anointing of Scottish Kings since the Dark Ages was not used in the service since it had already been carried off to London by the English and placed in Westminster Abbey as a trophy by Edward I.

Edward I, incensed at what he saw as the Bruce's treachery, sent an English army north to deal with the renegade. The Scots army met them at Methven near Perth, but victory went to the English forces. Bruce was forced to seek refuge in the remote Scottish Highlands, there, like an injured fox run to the ground, he retreated into his lair, a cave where he was famously heartened by watching a persistent spider make six attempts to spin a web along the roof before finally succeeding, which inspired Robert to continue his heroic struggle against English domination.

King Robert decided to dispatch his family to the Orkney Islands for their greater safety. Elizabeth de Burgh and other members of his family were captured by the English en-route, and taken prisoner. His twelve year old daughter was imprisoned in the Tower and some of the female members of his family, including his sister, Christina, suffered the humiliation of being held suspended in cages in full public view by Edward. His three younger brothers, Thomas, Alexander and Niall were all executed.

This brutal treatment succeeded in making the Bruce more determined and resolute to eventually prevail. In 1307 he mounted a surprise attack on the English forces at Carrick. Edward sent another army north to deal with the rebel Scots. Robert again resorted to hiding in the hills and mounted a guerilla war. He was defeated by the Earl of Pembroke at Glen Trool in Galloway, but, refusing to be deterred, met him again at Loudon Hill where Bruce's military tactics won a much needed victory for Scotland. The indomitable Edward I decided to march up to Scotland yet again, to deal with the irksome miscreant Robert the Bruce himself.

Edward I, now aged and ailing, died at Burgh-on-Sands, Cumberland and was buried at Westminster Abbey, the mausoleum of the English Kings, with the epitaph 'The Hammer of the Scots'. So determined was he to utterly crush the Scots it was reported that he asked for the flesh to be boiled from his bones and the bones carried with the English armies into Scotland thereafter, a request which was not honoured by his son and heir Edward II.

Bruce called a Parliament at St. Andrews on 17th March, 1309, clearly exhibiting to the English by that action that he was now effective King of Scotland. Enboldened, Robert then went on the offensive and marching an army into northern England, regained those Scottish castles which were still in control of the English.

The Battle of Bannockburn

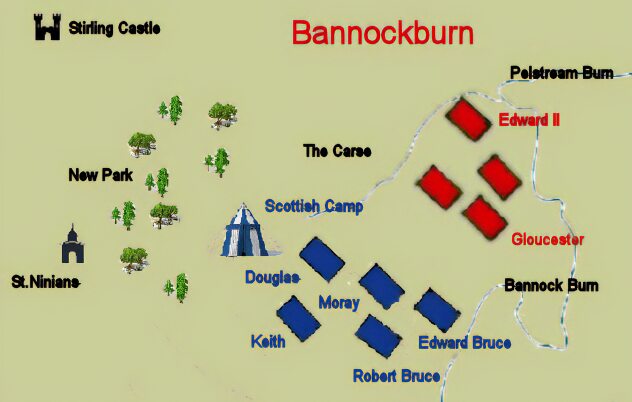

The new English King, the ineffectual Edward II, a pale shadow of his resolute father, responded belatedly by marching his forces into Scotland to meet Robert the Bruce. The two armies faced each other at the fateful battle of Bannockburn, near Stirling, on 24th June, 1314.

Statue of Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn

Edward II, said to be the great Edward I's only failure, was not the cunning military leader and general that his father had been. Although outnumbered three to one, the Bruce prepared for the impending battle carefully. The English would approach along the Roman road to Stirling crossing the Bannock Burn. Robert ordered pits to be dug beside the road. The Scottish army was then laid out in four groups using the lie of the land to its best advantage, to confine the vast English army within a very limited space.

On the morning of the battle, the Scots advance was lead by the King's brother, Edward Bruce. Walter the Steward and Thomas Randolph controlled the left, with Bruce and the Highlanders closely in the rear.

In the first encounter of the battle which was to be ever after renowned as Scotland's most famous victory, took place on the old road on Sunday, 23rd June. Sir Philip Mowbray, the commander of Stirling Castle, who had watched Bruce's preparations on the road, arrived at Edward II's camp early in the morning and warned the English king of the dangers of approaching the Scots directly through the New Park, but it was already too late. The vanguard under the Earls of Gloucester and Hereford were already marching on the Scottish army from the south. Following the line of the Roman road, they crossed the ford over the Bannockburn towards Robert's division at the opening of the New Park.

One of the first of the English knights to arrive at Bannockburn, Henry de Bohun, nephew of the Earl of Hereford, sighted the figure of the King of Scots on a highland pony, battle-axe in hand. Enthusiastically hoping to cover himself in glory, de Bohun seized the moment and charged. The Bruce sat motionless and calm until the point of Bohun's lance was only feet away, then he pulled his horse quickly aside and delivered a shattering blow which succeeded in carving both de Bohun's helmet and skull in two. This pre-battle encounter and Bruce's bravery has become legendary. On returning to his army, he complained that he had broken the shaft of his "good battle-axe" on Bohun's skull.

Heartened by the encounter, Bruce's division engaged the main English force. Fierce fighting ensued, during which the Earl of Gloucester was unhorsed, after which the knights of the vanguard were forced to retreat to the Tor Wood. Another English cavalry force under the command of Robert Clifford and Henry de Beaumont skirted the Scottish position to the east and rode towards Stirling, advancing as far as St. Ninians. The Bruce saw the manoeuvre and ordered Randolph's schiltron to intercept them. The English cavalry horsemen failed to overpower the Scots spearmen and the English squadron was broken.

On the second day of the battle, fought on 24th June, the English army was still approaching Stirling from the south as Bruce's preparations had made the direct approach to Stirling too hazardous. Edward ordered the army to cross the Bannockburn to the east of the New Park. Soon after daybreak, the Scots spearmen advanced on the English.

Battle of Bannnockburn

As the Scots drew nearer, they halted and knelt in prayer. Edward II is said to have exclaimed "They pray for mercy!" "For mercy, yes," one of his attendants replied, "But from God, not you. These men will conquer or die." Gloucester, asked the king to hurry, at which Edward accused him of cowardice. Infuriated, Gloucester led a charge against the leading Scots spearmen, under Edward Bruce. He was killed in the forest of Scottish spears, along with some of the other knights.

Bruce then issued orders for the whole Scots army to advance into a bloody push against the disorganised English mass, fighting side by side across a single front. the English were now so tightly packed that if a man fell, he risked being immediately crushed underfoot or suffocated, the English and Welsh longbowmen could not fire for fear they would hit their own men. After a while they moved to the side of Douglas's division and began firing into its left, but the Scottish cavalry dispersed them. The fleeing archers then caused the English infantry to begin to flee.

Later the knights also began to flee back across the Bannockburn. As the English formations beginning to break up, a great shout was heard from the ranks of the Scots army, "Lay on! Lay on! Lay on! They fail!". Bruce's camp followers then charged forward. The English mistook this for a fresh reserve and abandoned all hope. The English forces north of the Bannockburn fled. Some attempted to cross the River Forth where most drowned, others tried to retreat across the Bannockburn, they were pursued by the exultant Scots, and mass slaughter ensued, many died in the Bannock burn which was now ran red with blood, congested with the corpses of English dead.

On realising continued resistance was futile, Edward II, guarded by a company of knights, fled towards Stirling, but the town refused to admit him. The King of England was forced into a hasty and ignominious flight to Linlithgow. He finally made it back across the border to safety, but had been thoroughly humiliated. The rest of the English army tried to escape to the safety of the border, which lay ninety miles to the south. Many were killed by the pursuing Scottish army or by the inhabitants of the countryside that they passed through. Robert the Bruce had won a famous and resounding victory and was now the incontestable King of Scotland.

King Robert now now faced with the difficult tasks of attempting to obtain the King of England's recognition of him as King of an independent Scotland, having an heir to the Scottish throne and getting the Pope to lift his excommunication for the murder of Comyn, none of which was to prove easily achieved.

Robert's only child was a daughter, Marjorie, born of his first marriage. Fearing to leave the crown in the hands of a woman, unheard of at the time, the Scottish Parliament decreed that in the event of the king dying without a male heir the throne of Scotland should pass to his younger brother Edward Bruce.

Edward Bruce himself had designs of his own on Ireland and accordingly lead a campaign into that country. Robert ventured to Ireland in support of his brother. Edward was killed in battle at Dundalk, leaving the Scottish throne bereft of a successor. Robert was descended from the Gaelic royalty of Scotland and Ireland on his mother's side. His Irish ancestors included Eva of Leinster (d.1188), whose own ancestors included Brian Boru of Munster and the kings of Leinster.

He hoped to form a Gaelic alliance between Scottish-Irish Gaelic populations, with himself at its head. In a letter to the Irish chiefs, where he calls the Scots and Irish collectively nostra nacio (our nation), stressing the common language, customs and heritage of the two countries:-

' Whereas we and you and our people and your people, free since ancient times, share the same national ancestry and are urged to come together more eagerly and joyfully in friendship by a common language and by common custom, we have sent you our beloved kinsman, the bearers of this letter, to negotiate with you in our name about permanently strengthening and maintaining inviolate the special friendship between us and you, so that with God's will our nation may be able to recover her ancient liberty.'

The Declaration of Arbroath

Since Marjorie Bruce had died in childbirth some two years previously, her young son, Robert Stewart, was appointed as his grandfather's heir. In 1320 Bruce's second wife, Elizabeth de Burgh, the daughter of the powerful Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, after many years of being barren, conceived and gave birth to a daughter, followed in March, 1324, by a long awaited son and heir, christened David, for the Bruce's direct ancestor, David I.

Edward II, in common with his father before him, stubbornly refused to accept Bruce as de facto King of Scotland. To curb what they saw as his arrogance the Scots raided and pillaged northern England.

The English King reacted by amassing an army and marching into Scotland. Wily as ever, Robert embarked on a 'scorched earth' policy, laying waste the land before the English army who by the time they reached Edinburgh were starving and forced to return home. The Pope continued to refuse to recognise Robert as the lawful King of Scotland.

The Declaration of Arbroath

In April, 1320, the Declaration of Arbroath was signed by eight Scottish Earls and forty-five barons at Arbroath Abbey. It was a dignified plea to the Pope to recognise Scotland as an independent nation with Bruce at its leader. It asserted proudly:- "For, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom - for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself." Four years later the Pope addressed Bruce as King of Scotland.

With the inexorable march of time, an enemy not even he could defy, the great Robert the Bruce, now in his fifties, grew increasingly ill and infirm. Though purported to have been affected with leprosy, it seems more likely that that he was suffering from scurvy, a common complaint at the time. After suffering a stroke and on his deathbed, Robert knew he would be unable to fulfill his solemn vow to go on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He asked his life-long friend, Sir James Douglas, to carry his heart there instead. The greatest of Scotland's Kings died on 7th June, 1329 at the manor of Cardross, Dunbartonshire and was interred at Dunfermline Abbey. He was succeeded as King of Scotland by his son David Bruce

The tomb of the Robert the Bruce

The tomb of the Robert the Bruce, Dunfermline Abbey

In the year following Robert the Bruce's death, the faithful James Douglas set out for the Holy Land in fulfillment of his oath to the dying King, taking his heart with him in a silver casket.

The tomb of the Robert the Bruce, Dunfermline Abbey

In the course of his journey, while staying in Teba, Spain, the village was attacked by Moors. Douglas, in the thick of the fighting and deserted by his Spanish allies, threw the heart of the Bruce deep into the melee, biding it "Go first as thou hast always done." Douglas himself was killed in the ensuing fighting and his body was returned to his native Scotland. The heart of Robert the Bruce was carried back to Scotland by Sir William Keith of Galston, where it was finally laid to rest at the Abbey of Melrose.

Most of Robert's tomb was destroyed during the Scottish Reformation, but on 17th February 1818, workmen employed to build a new parish church on the site of the eastern choir of Dunfermline Abbey discovered a tomb before the site of the high altar of the former abbey. The tomb was covered by two large stones, a headstone and a larger stone measuring around six feet (182 cm) in length. On removing the stones, they uncovered the remains of an oak coffin containing a skeleton enclosed in two layers of lead, covered by a shroud of cloth of gold. The sternum (breastbone) of the skeleton had been split open and the skull wore a lead crown. In the debris around the grave, fragments of black and white marble were found, which were linked to Robert the Bruce's recorded purchase of a marble sarcophagus.

The remains were taken from the coffin and, together with the deteriorating lead shroud, were inspected by James Gregory and Alexander Monro, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh. The skeleton was attributed to Robert I on the basis of the sawn sternum, a procedure carried out after death to remove his heart in accordance to Robert's wish to have it carried by Sir James Douglas on Crusade. The bones were measured and drawn, and a plaster cast was taken of the skull by artist William Scoular. The cast confirmed that Robert suffered the loss of his upper incisors and associated alveolar maxillary bone. These features have been interpreted by V. Moller-Christiansen and R.G. Inkster, authorities on the osteological appearance of leprosy, as typical of leprosy. Robert the Bruce's skeleton was measured to be 5 feet 11 inches (180 cm). It was estimated that he probably would have stood at around 6 feet 1 inch (186 cm) tall as a young man, almost as almost as tall as King Edward I of England ( who was 6 feet 2 inches tall 188 cm).

Robert the Bruce's remains were re-interred in Dunfermline Abbey on 5 November 1819 in a new lead coffin. Richard Neave from the University of Manchester recreated his face from the cast made of his skull.

The Ancestry of Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce

Father: Robert the Bruce, 6th Lord of Annandale

Paternal Grandfather: Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale

Paternal Great-grandfather: Robert de Brus, 4th Lord of Annandale

Paternal Great-grandmother: Isobel of Huntingdon

Paternal Grandmother: Isobel de Clare

Paternal Great-grandfather: Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Hertford and Gloucester

Paternal Great-grandmother: Isabel Marshal

Mother: Marjorie, Countess of Carrick

Maternal Grandfather: Niall, Earl of Carrick

Maternal Great-grandfather: Nichol (Cailean or Colin)

Maternal Grandmother: Margaret Stewart, Countess of Carrick

The Family of Robert the Bruce

Married (1) Isabella of Mar -

(1) Marjorie Bruce (1296 - 2 March 1316) married Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland

(p)Issue :-

(i) Robert II of Scotland (1316 - 19 April 1390)

Married (2) Elizabeth de Burgh

(2) Matilda Bruce married (1) Thomas Isaac (2) Richard de Kelso,

(3) Margaret Bruce married William de Moravia, 5th Earl of Sutherland

Issue:-

(i) John de Moravia

(4) David II of Scotland (5 March 1324 - 22 February 1371)

(5) John, born October 1327 died young.

Illegitimate children of Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce also had six acknowledged illegitimate children:-

(1) Sir Robert, died 1332 at the Battle of Dupplin Moor

(2) Walter, of Odistoun on the Clyde

(3) Margaret, married Robert Glen

(4) Elizabeth, married Sir Walter Oliphant of Aberdalgie

(5) Christina of Carrick

(6) Nigel of Carrick, died 1346 at the Battle of Neville's Cross.