Circa 1035 - 1072

The legendary Hereward the Wake, the guerrilla leader who headed Anglo- Saxon resistance to William the Conqueror for five years has been called one of history's "greatest Englishmen".

The earliest references to his parentage are found in the Gesta Herewardi, which records he was the son of Edith, a descendant of Oslac of York. It is also been stated that Leofric, Earl of Mercia and his wife Lady Godiva were Hereward's parents, however, little credence is given to this theory. Abbot Brand of Peterborough is said to have been the uncle of Hereward. Recent research by Peter Rex has put forward the plausible theory that Hereward may have been the son of a prominent Anglo-Danish magnate called Asketil, the brother of Abbot Brand.

Hereward the Wake

His contemporary, Leofric the Deacon described Hereward as- 'comely in aspect, very beautiful from his yellow hair, and with large grey eyes, the right eye slightly different in colour to the left ; but he was stern of feature, and somewhat stout, from the great sturdiness of his limbs, but very active for his moderate stature, and in all his limbs was found a complete vigour. There was in him also from his youth much grace and strength of body ; and from practice of this when a young man the character of his valour showed him a perfect man, and he was excellently endowed in all things with the grace of courage and valour of mind.....'

The Domesday Book confirms that a man named Hereward held lands at Witham on the Hill and Barholm with Stow in the southwestern corner of Lincolnshire as a tenant of Peterborough Abbey. Before his exile, Hereward had lands as a tenant of Croyland Abbey at Crowland, eight miles to the east of Market Deeping in the neighbouring fenland.

Known in his own time as Hereward the Outlaw, the epithet "the Wake" is first mentioned in the late fourteenth-century Peterborough Chronicle, which could either derive from 'watchful' or from the Wake family, Norman landowners who acquired his lands in Bourne, Lincolnshire, after his death, they claimed descent from Hereward's daughter by his second wife, Alftruda.

Hereward the Wake

Primary sources on Hereward's exploits are either brief or sometimes enigmatic. They consist of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, the Domesday Book, the Liber Eliensis (Book of Ely), and much the most detailed, the Gesta Herwardi Saxonis ('Deeds of Hereward the Saxon'), compiled by monastic scholars in the eleventh century.

Hereward, by all accounts, a hot-headed young man, was exiled from England at the age of eighteen for disobedience to his father and was declared an outlaw by the Saxon King Edward the Confessor. After spending some time in military activity on the continent as a mercenary for the Count of Flanders, Hereward returned to England following the Norman conquest, either in late 1069 or 1070 to discover his family's lands had been confiscated and given to the Norman Ivo de Taillebuis and his father and brother killed, his brother's decapitated head was placed on a spike at the entrance to his house.

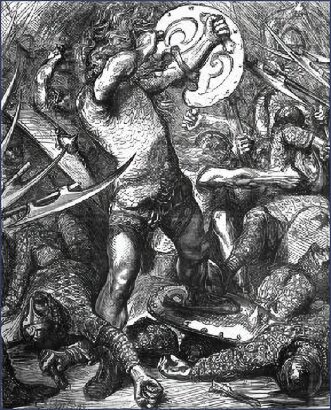

Overhearing Normans ridiculing his countrymen at a drunken feast, Hereward exacted a bloody revenge for his family, with the aid of only one follower, he is said to have killed fourteen of them. The next day fourteen Norman heads had replaced that of his brother at the gate. He then went to Peterborough Abbey where he was knighted by his uncle Abbot Brand. After returning briefly to the continent while the heated situation cooled, he returned again to England.

The Aldreth Causeway

In 1070, Hereward took part in a rebellion against Norman rule which centred on the Isle of Ely. The Danish king Sweyn Estrithson sent a small army to try to establish a camp on the Isle of Ely, where Hereward joined them. Brand had been replaced at Peterborough Abbey by a Norman abbot, Turold of Fecamp. With the aid of the Danes, ‘Hereward and his crew’ stormed and sacked Peterborough Abbey, claiming that he wished to save the Abbey's treasures from the rapacious Normans.

William the Conqueror led an army to Ely, where Hereward, joined by a small army led by Morcar, the former Saxon Earl of Northumbria, made a desperate stand. Ely at that time was an island in the fenland, William was foiled on three occasions by Hereward in his attempts to build a causeway across the impassable marshes, known as the Aldreth Causeway. However, during William's first attack the weight of the troops on the bridge was so great that the causeway sank and many soldiers drowned.

The legends surrounding Hereward state that the third time, while William was encamped at Brandon, Hereward rode there, meeting a potter, whom he persuaded to exchange clothes, in disguise and carrying their potter's wares, he daringly managed to enter William's camp and overheard his plans. William even went as far as employing a witch to curse the band of Saxon rebels. Following the construction of William's third causeway, his troops proceeded along it in an attempt to take Ely, Hereward's men, who lay hidden in the reeds, set fire to the area, engulfing the Normans in flames, those who tried to escape were either drowned or killed by Anglo-Saxon arrows.

On the eighth day, they all advanced to attack the island with their entire force, placing the witch in an elevated position in their midst. Once mounted she harangued the isle and its inhabitants for a long time, denouncing saboteurs and suchlike and casting spells for their overthrow... And when she had gone through this disgusting ceremony three times, as she had proposed, the men who had hidden all around the swamp... set the reeds on fire' -Gesta Herewardi.

The Normans then bribed Abbot Thurstan of Ely to reveal a safe path across the marshes, which resulted in Ely at last being taken. Morcar was captured and imprisoned, but Hereward managed to escape into the wild fenland.

Several conflicting accounts exist as to Hereward's fate thereafter, the Gesta Herewardi states that while attempting to negotiate with William he was provoked into a fight which led to his capture and imprisonment, however, he was later liberated by his friends while in the course of being transferred from one castle to another. Hereward's former gaoler persuaded the king to negotiate again, and he was eventually pardoned by William. The Estoire des Engleis, written by Geoffrey Gaimar claims Hereward lived for some time as an outlaw in the Fens, but that as he was on the verge of making peace with William, he was set upon and killed by a group of Norman knights. Even after his death, people still visited a wooden castle in the Fens that was known to the peasants as Hereward's Castle.

Waltheof of Northumbria PreviousNext Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria