The Archealogical Dig

On the 25th August 2012 an archaeological project undertaken by Leicester University, in partnership with the Richard III Society and Leicester city council, began with the aim of discovering whether Richard III's remains still lie buried at the site of the Greyfriars Franciscan Friary. The friary had been lost for centuries but was believed to be situated beneath a social services car park, which was located using historic maps.

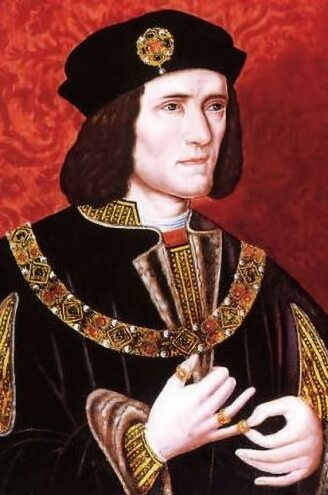

Richard III

The Greyfriars Project, which attracted extraordinary global media attention, unearthed the remains of the medieval church, where Richard III is recorded as being buried after his death at the Battle of Bosworth. Medieval finds from the dig include inlaid floor tiles from the cloister walk of the friary, elements of the stained glass windows of the church and a stone frieze believed to be from its choir stalls. They also found paving stones which are said to form part of a garden which belonged to a mayor of Leicester, Robert Herrick, where, historically, it is recorded that there was a memorial to Richard III. In the seventeenth century Christopher Wren, father of the architect recorded seeing a 3 feet high stone pillar in the garden with the inscription: "Here lies the body of Richard III sometime King of England", which post-dated reports that the body had been thrown into the River Soar when the friary was dissolved under Henry VIII.

During the third week of the dig on the 12th of September, 2012, archaeologists announced that human remains have been found in the area of the choir. Richard Taylor from the University of Leicester commented "What we have uncovered is truly remarkable and today we will be announcing to the world that the search for King Richard III has taken a dramatic new turn." Lead archaeologist Richard Buckley said, 'We were very lucky it was a car park, and the remains, at the entrance to the choir, were just under the trench we dug, when there were several buildings at the friary."

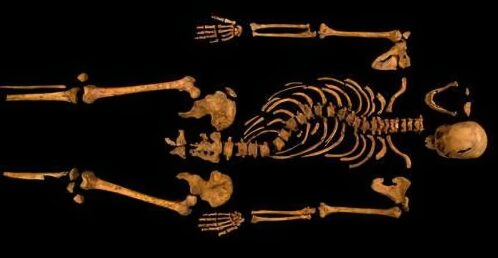

The male skeleton, which was buried in a grave without a coffin. underwent an initial examination which revealed spinal abnormalities. It is thought the individual would have had severe scoliosis " an individual form of spinal curvature, which makes his right shoulder visibly higher than his left shoulder." The skeleton was not a hunchback.

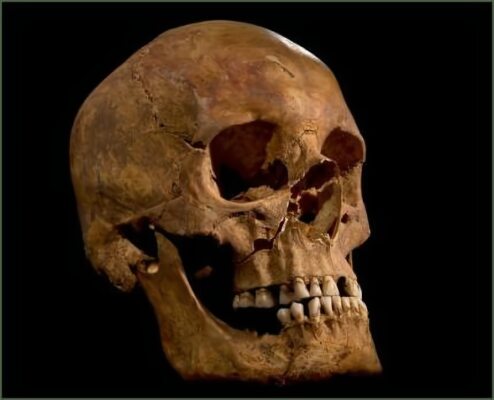

What was thought to be a barbed metal arrowhead was found between vertebrae of the skeleton's upper back, (but on closer examination this turned out to be a Roman nail) and the skull appears to have suffered significant near-death trauma. A bladed implement appeared to have cleaved part of the rear of the skull. The skull injury appears consistent with, although not certainly caused by, an injury received in battle. Richard was hacked down at Bosworth after being surrounded by his enemies and one historical account suggests that the blow which finally felled him was so hard that fragments of his helmet were left in his skull.

The Skeleton of Richard III

DNA tests were conducted, the remains were tested for a match with Canadian born Michael Ibsen, who shares the same mitochondrial DNA with Richard III. His mother, Joy Ibsen, traced by John Ashdown-Hill, is a direct descendant in the female line from Richard's elders sister, Anne of York and the King's 16th generation grand-niece. Mitochondrial DNA is passed directly down the female line. Similar techniques were used to identify the remains of Czar Nicholas II and other members of the Russian royal family, who were killed in 1918 during the Russian Revolution.

The results of tests on the Y DNA of Richard's skeleton threw up an infidelity surprise. Five anonymous donors, who are male-line descendants of the Dukes of Beaufort, who claim descent from the Plantagenets through John of Gaunt (third surviving son of Edward III), donated DNA samples which should have matched Y chromosomes extracted from Richard's bones, as Richard descended in the male line through Edward III's fourth surviving son, Edmund, Duke of York. but failed to do so. Four of the Duke of Beaufort's relatives were found to belong to Y-haplogroup R1b-U152 (x L2, Z36, Z56, M160, M126 and Z192)13, 14 with STR haplotypes being consistent with them comprising a single patrilinear group. One individual (Somerset 3) belonged to haplogroup I-M170 (x M253, M223) and therefore could not be a patrilinear relative of the other four, indicating that a false-paternity event had occurred within the last four generations. King Richard's Y DNA was found to be the rare G-P287, with a corresponding Y-STR haplotype. The analysis shows the break occurred somewhere along the male line linking Richard III and Henry Somerset, the 5th Duke of Beaufort (1744-1803). It is not known where the chain from King Edward III this false paternity event occurred, or whether it occurred in Gaunt's line or the York line.

It was rumoured that Richard III's grandfather, Richard, Earl of Cambridge was not the true son of Edmund Duke of York. Richard Earl of Cambridge's mother, Isabella of Castille, indulged in an affair with King Richard II's half-brother, John Holland, 1st Duke of Exeter (died 1400), the son of Joan 'Fair Maid of Kent' by her first husband Thomas Holland, 1st Earl of Kent. It has been suggested that since Richard received no lands from his father, and received no mention in either his father's or his brother's wills, he may have been the child of his mother's affair with Holland. However, this remains unproven. If it were the case it would not invalidate the Yorkist claim to the throne, since this derived from their female line descent from Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, the second surviving son of Edward III. The false paternity event could equally have occurred in the Beaufort line, which contains far more links in the chain from Edward III, a false-paternity event could have occurred in any of the 19 generations separating Richard III and the 5th Duke of Beaufort.

A formal announcement by Leicester University was made on the results of the tests on Monday, 4th February 2013, at which the project's lead archaeologist Richard Buckley stated "It is the academic conclusion of the University of Leicester that the individual exhumed at Grey Friars, Leicester, in August 2012, is indeed Richard III, the last Plantagenet King of England." DNA, genealogy, carbon dating and other scientific methods were used to confirm the identity of the former king beyond any doubt.

Skull of Richard III

News of a second anonymous relative was also revealed. Michael Ibsen, whose DNA matched exactly that of the king's remains, said he reacted with "stunned silence" when told the closely-guarded results on Sunday. Dr Turi King, who carried out the DNA analysis, stated "The type of DNA we extracted is extremely rare, shared by only a few per cent of the population. Taken together with the other evidence, it is a very strong and compelling case.” The bones had also undergone radiocarbon dating which indicated the date of death as sometime between 1485 and 1550.

In an attempt to solve the mystery of in which line of descent the non-paternity event occurred, geneticists extracted the DNA of Patrice de Warren, a male-line descendant of an illegitimate son of Geoffrey, Count of Anjou (1113 - 1151), the father of Henry II. However, the test revealed that De Warren's Y chromosome didn't match that of Richard III or Henry Somerset. Schürer and King now plan to conduct genetic testing on other de Warrens in the US and Australia, and men in the extended Somerset family. "The idea is to have a pincer movement and tackle it on several different fronts," said Schürer. "We're not going to give up the quest.

Richard's Skeleton

Archaeologists stated that the remains bore the marks of ten injuries inflicted shortly before death, 8 to the skull and 2 to the body. The contemporary chronicles state that he was urged to flee following the desertion of some of his followers and the collapse of his vanguard. Polydore Vergil, one of the early chroniclers of the battle, states that Richard replied that 'on that day he would make an end either of wars or of his life, such was the great boldness and great force of spirit in him’. Richard instead chose to lead a charge straight at Henry Tudor, killing several men and toppled Henry's standard, killing his standard-bearer William Brandon, and unhorsed the jousting champion, Sir John Cheney, who stood in his way, thrusting him to the ground and forcing a path for himself through the press of steel.

Polydore Vergil recorded that 'King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies.' According to the Burgundian chronicler Jean Molinet, Richard's horse became stuck in a marsh and then 'unhorsed and overpowered, the king was hacked to death by Welsh soldiers'. Molinet adds that a Welshman struck the death blow with a halberd. The contemporary Welsh poet Guto'r Glyn also states that a Welshman, Rhys ap Thomas, or one of his men, delivered the fatal blow. Even after Richard was dead, the blows continued on his battered body, one source describes how Richard’s head was battered to the point that his basinet was driven into his head, ‘until his brains came out with blood’.

The tests revealed " He was killed by one of two fatal injuries to the skull, one possibly from a sword and one possibly from a halberd. The base of the skull had been sliced off by a blow, believed to be from a halberd, an axe blade mounted on a wooden pole, which was swung at Richard at very close range. The blade probably penetrated several centimetres into his brain and he would have been unconscious at once and dead almost as soon. There were other, non-fatal injuries to the cranium and the face that could have been caused by knives or daggers.

The body of King Richard III, which was recovered from the pile of corpses around Henry's banner, was treated with much indignity. Trussed naked over a horse and besmirched with mud, it was borne in a parade to Leicester, a sad spectacle. It was exposed for two days at the Church of the Greyfriars at Leicester, where Richard III was later unceremoniously buried. Buckley revealed that the position of the hands suggested that they might have been bound together.

Reconstructed face of King Richard

Osteoarchaeologist Dr Jo Appleby discussed a series of "humiliation injuries" inflicted on Richard III after his death. These included a dagger mark on his ribcage and a sword wound on the inside of the pelvis from a violent injury to the right buttock. She said: "This injury was caused by a thrust through the right buttock, not far from the midline of the body. "These two wounds are also likely to have been inflicted after armour had been removed from the body. This leads us to speculate that they may also represent post-mortem humiliation injuries inflicted on this individual after death." Historical accounts report that after Richard's defeat at Bosworth, his body was stripped, thrown over the back of a horse to be taken back to Leicester. It is believed that the "humiliation injuries" may have been inflicted at this time.

The skeleton was that of a man whose age at death was between 30 and 33, which is consistent with the age of the 32-year-old king. The skeleton revealed idiopathic adolescent-onset scoliosis which developed after the age of 10. Scoliosis is defined as a lateral curvature of the spine greater than 10 degrees accompanied by vertebral rotation. Richard was around 5 feet 8 inches tall, although his disability meant he would have stood up to a foot shorter and his right shoulder would be higher than the left.

It also revealed that the individual had a high protein diet, including significant amounts of seafood. Dr Appleby also said that the skeleton bore no evidence of a withered arm. She said: "The analysis of the skeleton proved that it was an adult male, but with an unusually slender, almost feminine, build for a man. This is in keeping with historical sources which describe Richard as being of very slender build. "There is, however, no indication that he had a withered arm; both arms were of a similar size and both were used normally during life." The DNA analysis, published in the journal Nature Communications, also reveals that Richard III would have been blue-eyed with blond hair as a child.

Layers of muscle and skin were added by computer to a scan of the skull by Caroline Wilkinson, professor of craniofacial identification at the University of Dundee, the result was made into a three-dimensional plastic model which was unveiled by the Richard III Society at the Society of Antiquaries in London. Researchers have also attempted to reconstruct the voice of the king. Dr Philip Shaw, from the University of Leicester, studied the king's use of grammar and spelling in contemporary letters, and concluded that the king's accent "could probably associate more or less with the West Midlands."

The Reburial of Richard III

Researchers had stated that if the king was found, one option would be for his remains to be interred at Leicester Cathedral. Campaigners from York said the remains, should they prove to be the king, ought to come to them as Richard had expressed a desire to be buried at York Minster. Following a discussion about where the remains should eventually be laid to rest, the government has since confirmed that they will be interred in Leicester Cathedral.

A service to mark the reburial of King Richard III was held at Leicester Cathedral on 26 March 2015. The Archbishop of Canterbury, The Most Rev Justin Welby, presided over the service. Sophie, Countess of Wessex, represented the Queen and the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester were among the guests. Actor Benedict Cumberbatch, a distant relation of the king, read a poem by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy. Also present at the ceremony were Michael Ibsen and Wendy Duldig, the descendants of Richard's sister Anne of York, both of whom had provided DNA to identify the king's remains.

The king's tomb consists of a block of Swaledale stone, with a deeply incised cross, on a plinth of dark Kilkenny marble carved with Richard's name, dates, motto - loyaulte me lie (loyalty binds me) - and coat of arms.

Images courtesy of the University of Leicester

Sources

King, T. E. et al. Identification of the remains of King Richard III. Nat. Commun. 5:5631 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6631 (2014).

Henry Stafford PreviousNext Burial Places