Winchester Cathedral

An exciting new project at Winchester Cathedral plans to examine the remains of several of England's Anglo-Saxon and Danish kings.

The contents of six mortuary chests, kept at the cathedral for centuries, contain the remains of 11 or 12 people are to be analysed. These include the purported remains of Cynegils, the first Christian king of Wessex (reigned 611-643), Cynewulf, King of Wessex (643-672), King Egbert (802-839), the first King of all England, and his son Ethelwulf (839-856), the father of Alfred the Great, King Edred (946-955) the grandson of King Alfred, Edred's nephew King Edwy (955-959), Canute, King of England (1016-1035), Norway and Denmark (d.1035) and his wife Emma of Normandy (also queen consort to the Saxon king Ethelred 'the Redeless'), and the Norman king, William Rufus (1087-1100), who was killed by a stray arrow during a hunting expedition in the New Forest in 1100. Canute and Emma's son Hardicanute (1040-1042) is now buried in the wall of the choir screen, rather than in a mortuary chest.

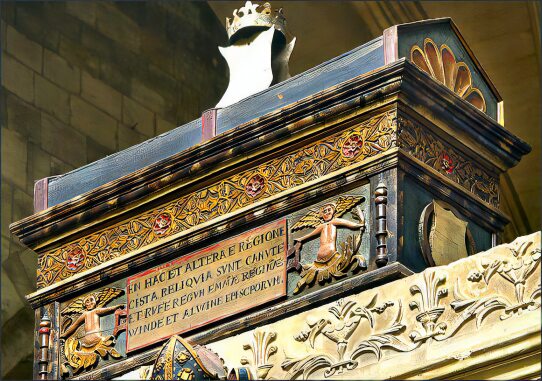

The Winchester Mortuary Chests

Its also believed the chests contain the remains of the Anglo-Saxon Bishops Wini (died 670) and Alfwyn (d.1047) and Archbishop Stigand (d.1072). The identity of King Edmund, also buried in the chests is unknown. His date of birth has been omitted, he is thought not to be Edmund the Elder, who was buried at Glastonbury Abbey in Somerset. He is claimed by Thomas Rudborne in his 'Historia Major', to be the eldest son of Alfred the Great who was crowned in his father's lifetime but died in infancy. However neither the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle or Asser's Life of Alfred mentions this supposed son. An inscription on a stone, dating to the twelfth century and now set in the stone bench beneath the south presbytery screen of the cathedral reads 'Hic iacet Edmundus Rex Eþeldredi regis filius' (Here lies King Edmund, son of King Ethelred). Edmund Ironside, the son of Ethelred the Redeless is recorded to have been buried near his grandfather Edgar at Glastonbury Abbey but his bones may have been relocated to Winchester by his successor, Canute, who married his stepmother.

Alfred the Great, (reigned 875-899) and his son Edward the Elder (899-924) were also buried at the Old Minster but were later removed to Hyde Abbey, a section of pelvis, exhumed from an unmarked grave in the grounds of St Bartholomew, the medieval church where it is believed Alfred was reburied in the nineteenth century and stored in a cardboard box in Winchester museum has been dated by radiocarbon tests to between 895 and 1017 and may have belonged to King Alfred or Edward the Elder.

One of the inner chests

Many of the Anglo-Saxon and Danish Kings were originally buried in the 'Old Minster' at Winchester which was founded in 642 and was situated just to the north of the present Norman cathedral which replaced it. When the Saxon Minster was demolished, the Royal remains were exhumed and placed in mortuary chests around St. Swithun's Shrine around the high altar of the cathedral of the new building in the twelfth century by Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester, the brother of King Stephen. A document dating to the thirteenth-century states-

'In the year of Our Lord 1158 Henry, Bishop of Winchester, caused the bodies of the kings and bishops to be brought from the Old Minster into the new church, which were removed from an unseemly place and placed together in a more respectful manner around the altar of the blessed Apostles Peter and Paul.'

They survived the destruction of the Dissolution of the Monasteries and were placed in position along the decorative screen surrounding the presbytery of Winchester Cathedral in Tudor times. Mainly the work of Bishop Richard Fox, the chests are made from wood, which has been carved, painted and surmounted by crowns and shields. Earlier versions of the chests are displayed in the Triforium Gallery Museum in the cathedral.

There were originally eight chests, however, In 1642, during the Civil War, Cromwell's Roundhead soldiers, who entered the Cathedral after the battle of Cheriton, used the bones as missiles to shatter stained glass windows in the cathedral in the process of which two of the chests were smashed. The church officials, who had no way of determining which bones belonged to whom, later placed them back in the six remaining chests. When the chests were again opened for examination in Victorian times, earlier boxes were discovered to lie inside them.

Reconstruction of one of the faces of the teenage boys whose bones were discovered in the chests

The mortuary chests and their contents have recently been moved to the Cathedral's Lady Chapel and initial analysis has taken place on the chests themselves, with a view to their conservation as part of King's and Scribes: The Birth of a Nation, a three-stage exhibition to be held in the Cathedral's South Transept. A Heritage Lottery Fund grant has been applied to finance the project.

Speaking of the coming project, the Dean of Winchester, The Very Revd James Atwell stated "This is an exciting moment for the Cathedral when we seem poised to discover that history has indeed safeguarded the mortal remains of some of the early Saxon Kings who became the first monarchs of a united England. Winchester holds the secrets of the birth of the English nation and it does seem that some of those secrets are about to be revealed as future research continues. The presence of the bones in the Cathedral, where they would have been placed near the High Altar and the relics of St Swithun, remind us just how significant the inspiration of the Christian faith was for the foundation of our national life."

Preliminary findings from the Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit at the University of Oxford have been announced. It reveals that the bones originate from the late Anglo-Saxon and early Norman eras. Further research on the remains is to be carried out by the University of Bristol. The results of the radiocarbon dating were calibrated by estimating the ‘marine reservoir’ effect for each sample since high-status individuals ate large quantities of fish from the rivers and the sea which contain older radiocarbon. The age of the individuals was also determined by dental formation and attrition, changes to the bone surfaces and the closure of the cranial (skull) sutures. The skeletons were reassembled based on bone appearance and the estimated size and age of the individuals.

This project will involve historians, archaeologists, DNA experts, other scientists and art historians. Recent developments in forensic archaeology mean that it is now possible to examine the contents of the mortuary chests with a minimum level of disturbance to the remains. It is hoped that the research will record the contents of each chest, to determine how many people have remains buried within them, the dates in which they lived, and their physical characteristics, including sex, stature and age at death. Bristol University archaeologists will use DNA techniques, team leader Professor Mark Horton has stated: 'The preliminary findings are very exciting'.

The dispersed remains were analysed and radiocarbon-dated, to match the remains with the names of eight kings, two bishops and one queen whose names are on six mortuary chests. University of Bristol biological anthropologists discovered the chests contained the remains of at least 23 people, several more than originally assumed. The mixed bones were reassembled and analysing the sex, age and physical characteristics led researchers to conclude that the remains of a mature female could be those belonging to Emma of Normandy. DNA testing is being carried out to confirm the identity of all individuals.

A surprise find was the skeletons of two youths aged between 10 and 15, who died sometime between 1050 and 1150. Prof Kate Robson Brown stated that they were "almost certainly of royal blood". She added "We cannot be certain of the identity of each individual yet, but we are certain that this is a very special assemblage of bones," The findings, as well as a reconstruction of the suspected bones of Queen Emma, form part of a major Kings and Scribes: The Birth of a Nation exhibition which opens in late May 2019. A cathedral spokesman added: “These discoveries could place Winchester Cathedral at the birth of our nation and establish it as the first formal royal mausoleum.”

The continuing research is deepening our understanding of the early Anglo-Saxon kings and queens of England, and visitors can find out more about the project from 21 May when Winchester Cathedral launches its landmark National Lottery Funded exhibition Kings and Scribes: The Birth of a Nation. The bones of the female skeleton have been 3D printed and laid out as a key exhibit in the exhibition.

Uhtred the Bold PreviousNext Cynegils, King of Wessex