Queen of the Iceni

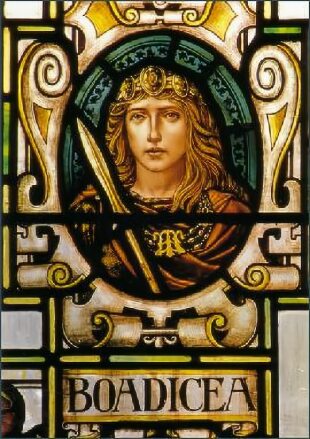

Boudicca, or Boadicea as she was known to the Romans, was the wife of Prasutagus, ruler of the Iceni tribe, who occupied roughly what is now Norfolk. Boudica was described by contemporaries as tall with flowing red hair below her waist, She was also said to have had a harsh voice and piercing glare, and wore a large golden neck ring, a multi-coloured tunic, and a thick cloak fastened by a brooch.

Boudicca

After the Roman conquest of southern England in 43 A.D., Boudicca's husband Prastagus ruled over the territories of the Iceni as an independent vassal of Rome. The Roman procedure at the time was that when a vassal king died the Romans took over the area. On his death in around 59 A.D., Prasutagus tried to side-step this by bequeathing his lands jointly to his daughters and the Roman Emperor, however, the lands of the Iceni were annexed to Rome and when Boudica protested she was flogged, her daughters were raped and the Romans seized the wealth of many of the Iceni.

In the year 60 or 61 A.D., when the Roman governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was conducting a campaign against rebels on Anglesey in north Wales, a stronghold of the Celtic druids who were making their last stand there, Boudica and the Iceni, in alliance with the Trinovantes and other neighbouring tribes, rose in revolt against the rule of Rome.

Striking at symbols of the hated Roman occupation, the British rebels marched on the poorly defended Roman colony of Camulodunum (Colchester), which was the former capital of the Trinovantes, the city was destroyed. The Roman Procurator, Decianus was forced to flee. The Britons besieged the temple to the former emperor Claudius for two days, regarded by the local native population as a citadel of everlasting tyranny, it finally fell after which the city was methodically demolished. Quintus Petillius Cerialis led the Legio IX Hispana, in an attempt to relieve the city, but suffered an overwhelming defeat with his infantry totally annihilated.

Hearing news of the uprising, Suetonius marched hastily along Watling Street to Londinium (London). Londinium was strategically abandoned by the rebels who burnt it down, no prisoners were taken and no mercy was shown, all those left within the city were slaughtered. Modern archaeology has revealed a thick red layer of burnt debris covering coins and pottery dating before AD 60 within the bounds of Roman Londinium. Skulls dating from the Roman era unearthed in the Walbrook in 2013 was potentially linked to victims of the rebels.

During the revolt of Boudicca, the Iceni performed sacrifices to the Celtic Goddess of revenge, Andraste. Dio Cassius describes a scene in which Boudicca released a hare from her gown - "Let us, therefore, go against (the Romans), trusting boldly to good fortune. Let us show them that they are hares and foxes trying to rule over dogs and wolves." When she (Boudica) had finished speaking, she employed a species of divination, letting a hare escape from the fold of her dress; and since it ran on what they considered the auspicious side, the whole multitude shouted with pleasure, and Boudica, raising her hand toward heaven, said: "I thank you, Andraste, and call upon you as a woman speaking to a woman ... I beg you for victory and the preservation of liberty."

The victorious rebels then turned on Verulamium (St Albans), a city largely populated by Britons who had cooperated with the Romans, which was also destroyed. In the three settlements destroyed, between seventy and eighty thousand people are said to have been killed.

Statue of Boudicca at Westminster

While Boudicca's exultant army continued their assault in Verulamium, Suetonius regrouped his forces, gathering an army of almost ten thousand men. He clashed with the Celtic army at the Battle of Watling Street, fought at an unidentified location somewhere along the Roman road now known as Watling Street. Most historians favour a site in the West Midlands. A site close to High Cross in Leicestershire has also been suggested, on the junction of Watling Street and the Fosse Way. Suetonius was heavily outnumbered by the Celts, but chose an advantageous position with dense woodland protecting his rear and a narrow defile in front.

Boudicca proudly addressed her army from her war chariot, stating that their cause was just, and the gods were on their side. She stressed that she, a woman, was resolved to win or die rather than live in slavery to the Romans. At the opening of the battle, the Romans killed thousands of Celts with volleys of heavy javelins known as pila as they charged uphill on the Roman lines. The Romans then advanced in a wedge formation, the Britons made attempts to flee, but were impeded by the presence of their own families, whom they had stationed in a ring of wagons at the edge of the battlefield, and were slaughtered. Tacitus provides an account of the final battle that relates to the women running about frantically, hair wild, naked and screaming. By the end of the day, 80,000 Iceni lay dead on the battlefield.

Most of the items found at Llyn Cerrig Bach can be seen in the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. The range and size of the Llyn Cerrig Bach collection is of great importance to our understanding of Iron Age weaponry, metalworking, tools and the development of art styles.

Much of our information regarding Boudicca is sourced from two Roman writers, Publius Cornelius Tacitus (A.D. 56-117) and Cassius Dio (A.D. 150-235). The Roman historian Tacitus reported that Boudica poisoned herself rather than be taken prisoner, though, in the Agricola which was written almost twenty years prior, he mentions nothing of suicide and attributes the end of the revolt to socordia ("indolence"); Dio states she fell sick and died and was given a lavish funeral. As a result of the rebellion, the Romans strengthened their military presence in Britain and also lessened the oppressiveness of their rule.

Arcaeological Evidence of Boudicca's Revolt

A thick layer of red soot has been unearthed in modern Colchester, a survival from the time when Boudicca set the city ablaze. The George Hotel, on High Street, has a glass pane in its basement which reveals the distinctive burnt red clay. An archaeological dig at Colchester found evidence to suggest every house had been carefully levelled, one by one, by the Iceni.

This archaeological layer is known as Boudicca's Destruction Horizon, with burnt artefacts from the period, many of which are displayed at Colchester Castle Museum, which now occupies the site of the Roman Temple of Claudius. Ahead from a bronze statue of the Emperor, which is thought to have come from the temple, was found at Rendham in Suffolk and is now housed in The British Museum.

An archaeological excavation at Gryme's Dyke, Colchester, a Roman-controlled earthwork, provided graphic evidence of the harsh treatment the Romans meted out to the native inhabitants of Colchester. Six humans skulls were unearthed, one of which displayed a deep gash, the result of a heavy sword blow to the head. Another of the skulls exhibited a severe fracture caused by a blunt instrument such as a sword pommel, in both cases the injuries that had been inflicted on these individuals had proved fatal. Further tests revealed that these were the remains of native Celts. It is believed that the heads had been impaled on stakes erected within the earthwork enclosure to act as a deterrent to others.

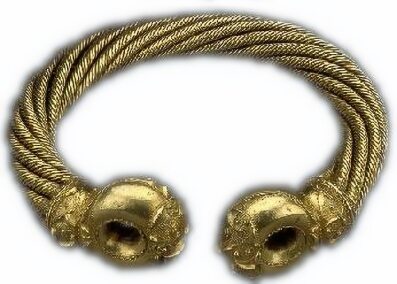

Celtic Torc

Verulamium Museum has reconstructions of Roman rooms, an impressive Roman and Iron Age archaeological collection of national and international significance including, among other treasures, weapons and armour of the period, a suit of Iron Age chain mail buried with the chieftain of the Catuvellauni tribe and a Roman helmet.

In common with Colchester, the main evidence for Boudicca's revolt in London is the presence of a charred archaeological layer dating to before 60 A.D. within the bounds of Roman Londinium. The layer, which is up to 30 cm thick in some areas, includes the remains of buildings burnt down by the rebels.

In the 1860s, excavations uncovered a large number of blackened Roman skulls, and almost no other bones, in the bed of the Walbrook, a subterranean river in London. It was a common custom of the Celts at the time to decapitate the enemy and keep their heads. It is thought that the Walbrook Skulls, maybe the heads of some of the Londoners massacred by Boudicca.

Cockley Cley, 3 miles South West of Swaffham, in Norfolk, has a reconstruction of an Iceni Village, which recreates the life of the Iceni in Britain just before the invasion of the Romans around 2000 years ago.

The Snettisham Hoard was unearthed in Norfolk between 1948 and 1973. The hoard consists of metal, jet and over 150 gold torc fragments, over 70 of which form complete torcs, dating from BC 70. Though the hoards origin is unknown, it is of sufficient high quality to have been a royal treasure of the Iceni. The Roman historian Dio Cassius, described Boudica wearing a magnificent gold neck ring. This was almost certainly a torc.

The Last Stand of the Druids PreviousNext Battle of Watling Street