The Celtic people

The history of the Celtic peoples stretches back thousands of years, the Celts first appear in history in the pages of Herodotus (480-408 B.C.), who referred to them as "Kelt-oi" and located them on the continent of Western Europe. The earliest European Celtic culture was in Hallstadt, Austria, and this was followed by the La Tene Celts in Switzerland. The idea of a 'Celtic' race is a modern concept, the peoples described as Celts were loosely tied by similar languages, religion, and cultural expression The first Celtic immigrants in Britain, probably arrived between 2000 and 1200 BC. These are known as the q-Celts and spoke Goidelic or Gaelic Celtic, q-Celtic derives from the differences between the early Celtic and Latin languages, which included the lack of an 'up in Celtic and an 'a' rather than the Italic 'o'. A later wave of Brythonic-speaking Celtic immigrants, who settled in England, Wales and the lowlands of Scotland are known as the p-Celts.

From surveys of measurements of the people in Britain, anthropologists conclude that "the darkest population forms the nucleus of each of the Celtic language areas which now remain". This dark Celtic speaking element are particularly to be found in "the Grampian Hills in Scotland, the wild and mountainous Wales (and Cornwall) and the hills of Connemara and Kerry and Western Ireland."

The geographer Strabo, who died 24 AD, described the tribes in the interior of Britain as taller than the Gaulish colonists on the coast and describes the men as warlike, passionate, disputatious, easily provoked, but generous and unsuspicious.

The Roman historian Tacitus described the Britons as being descended from people who had arrived from the continent, comparing the Caledonians of Scotland to their Germanic neighbours; the Silures of Southern Wales to Iberian settlers, and the inhabitants of Southeast Britain to the Gauls.

When going into battle, the men brushed their hair forward in a thick mass and dyed it red using a soap made of goat's fat and beech ashes, until they looked according to Cicero's tutor Posidonius, who visited Britain about 110 B.C., 'less like human beings than wild men of the woods.'

Diodorus recorded that:- 'Their aspect is terrifying...They are very tall in stature, with rippling muscles under clear white skin. Their hair is blond, but not naturally so: they bleach it, to this day, artificially, washing it in lime and combing it back from their foreheads. They look like wood demons, their hair thick and shaggy like a horse's mane. Some of them are clean-shaven, but others - especially those of high rank, shave their cheeks but leave a moustache that covers the whole mouth and, when they eat and drink, acts like a sieve, trapping particles of food...'

'The way they dress is astonishing: they wear brightly coloured and embroidered shirts, with trousers called bracae and cloaks fastened at the shoulder with a brooch, heavy in winter, light in summer. These cloaks are striped or checkered in design, with separate checks close together and in various colours. [The Celts] wear bronze helmets with figures picked out on them, even horns, which made them look even taller than they already are...while others cover themselves with breast-armour made out of chains. But most content themselves with the weapons nature gave them: they go naked into battle...Weird, discordant horns were sounded, (they shouted in chorus with their) deep and harsh voices, they beat their swords rhythmically against their shields.

The Celts were fond of ornaments, gold bracelets, rings, pins, and brooches, and beads of amber, glass, and jet. Their shields were the same round target that was still used by the Highland clans at the Battle of Culloden. Their war chariots, which held several people at a time, were made of wicker and drawn either by two or four horses. They wore bronze, sometimes horned helmets, only two of which have yet been found in Britain, the horned helmet from Waterloo Bridge and the helmet from the Merrick Collection

Iron age Celtic fort

The Celts scorned the use of armor and before about 300 B.C. preferred to fight naked. They were head-hunters and in battle he would sever the head of a fallen enemy and often hang it from their horse's necks. After battle the Celts displayed the severed heads of enemies. Julius Caesar describes the Brythonic Celts as dressed in leather skins and decorated with woad, a blue dye:'All the Britons dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue colour, and as a result their appearance in battle is all the more daunting. They wear their hair long, and shave all their bodies with the exception of their heads and upper lip'(Caesar). Some tattooed skin from a Scythian grave of this period suggests that the Celts may have been tattooed in blue.

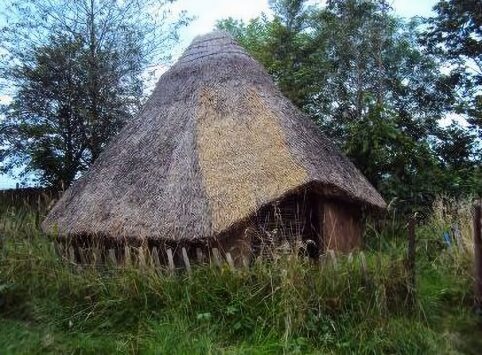

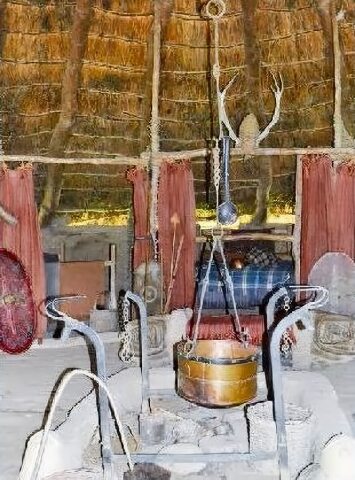

The Celtic tribes lived in roundhouses with conical thatched roofs of straw or heather. Roundhouses were the standard form of housing built in Britain from the Bronze Age throughout the Iron Age and well into the Roman period. The walls of these houses were made from local material. Houses in the south tended to be made from wattle and daub.

There are now many modern reconstructions of roundhouses to be seen throughout Britain. Butser Ancient Farm is an archaeological open-air museum located near Petersfield in Hampshire, southern England. Containing reconstructions of late prehistoric buildings such as Iron Age roundhouses. The prominent British archaeologist Mick Aston has stated that "Virtually all the reconstruction drawings of Iron Age settlements now to be seen in books are based" on the work at Butser Farm, and that it "revolutionised the way in which the pre-Roman Iron Age economy was perceived".

The roundhouses at Castell Henllys Iron Age hillfort, on the fringe of the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire, have been carefully reconstructed using the archaeological evidence found on the site. Archaeologists have been excavating the fort for over twenty years. Each of the upright poles which support the roofs have been positioned in the original post holes. There are four roundhouses and a granary at Castell Henllys and prehistoric breeds of livestock graze there. The site is an excellent resource for understanding the Iron Age in Britain. The first to be constructed, the 'Old Roundhouse' was reconstructed more than twenty years ago and is the longest standing reconstructed Iron Age roundhouse in Britain.

Roundhouses at Castell Henllys

Hillforts existed in Britain from the Bronze Age, but the majority of British hillforts date from the Iron Age, when they reached their heyday, between 700 BC and the Roman conquest of 43 AD. Varying from mere mounds to huge ramparts, these Dark Age fortresses dot the British landscape, vestiges of an age of warriors, sacrifice and ritual and murderous retribution. These large defensive enclosures protected by a series of steep ditches can usually be found occupying prominent hilltop positions. In times of attack, the local populace may have sought refuge within the hillforts.

DNA Evidence

The evidence from DNA studies is at odds with the modern perceptions of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon ethnicity. Evidence from genetic analysis would appear to indicate that the Anglo-Saxons and Celts were both small immigrant minorities.

Genetic evidence has revealed that three-quarters of the ancestors of Modern Englishmen came to the British Isles as hunter-gatherers, between 15,000 and 7,500 years ago, after the melting of the ice caps but before Britain was divided from the mainland and became islands. Britain's subsequent separation from Europe has preserved a genetic time capsule of southwestern Europe during the ice age. Estimates calculate the DNA from later invaders accounts for as little as 20 per cent of the gene pool in Wales, 30 per cent in Scotland, and about a third in eastern and southern England.

In 2007 Bryan Sykes, Professor of Human Genetics at the University of Oxford, published an analysis of 6000 Y DNA samples, the chromosome passed down only in males, in his book 'Blood of the Isles'. Sykes argued for a significant migration of peoples from the Iberian peninsula into Britain and Ireland. In 2010 several major Y DNA studies produced more complete data, which revealed that the oldest male lineages had mostly migrated into Britain from the Balkans, and ultimately from the Middle East, not from Iberia.

In a whole-genome mitochondrial DNA database, which charts female lineage, published in 2012, it was concluded that the most ancient mtDNA lineages derived from a Middle Eastern migration into Europe during the late Ice Age around 19-12 thousand years ago. They made claims that this population came from the Anatolian Plateau and later spread to Franco-Cantabria, the Italian Peninsula and the East European Plain. From these three areas, these peoples then repopulated Europe.

There are clear signs of the Germanic influx of the Anglo-Saxons in parts of Britain but there was a continuing indigenous element to English paternal genetic makeup, a substantial amount of an 'ancient British' DNA which most closely matches the DNA of modern inhabitants of France and Ireland. Bryan Sykes has stated that only 10 per cent of men "now living in the south of England are the patrilineal descendants of Saxons or Danes, that figure rising to 15 per cent north of the Danelaw and 20 per cent in East Anglia". The idea that the Britons were eradicated in England, culturally, linguistically and genetically, by invading Angles and Saxons, appears to be incorrect and it seems they were more assimilated into Anglo-Saxon society, eventually becoming Englishmen.

Related pagesThe Celtic people PreviousNext The Celtic Tribes